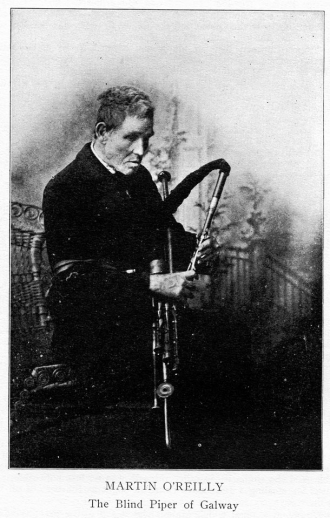

Martin O’Reilly was an extraordinary man and an extremely talented piper. O’Reilly was born in Galway City in 1829. The exact location of his home is not known for certain, but it was possibly in Sickeen or Eyre Street; some say it was on the junction of both streets. He suffered from blindness from birth or shortly afterwards. Nevertheless, this didn’t affect his wonderful talent as an Uilleann piper. He operated a small dance hall in Sickeen for a number of years. There is an old stone building with a ‘later galvanize’ roof located there and according to tradition, this was the actual dancehall. Past generations of local people mentioned this was O’Reilly’s place in the late nineteenth century. While the building is small, one must remember that it was a time when dances ‘Hooleys’ could be held in kitchens. It was said long ago that in order to dance to the music of the piper, one had to place a coin in his hat, ‘Pay the Piper’. The amount of money given determined how long one could dance. According to one source, his dance hall was eventually closed down by the clergy because it became a meeting place for young men and women. However, another report blames emigration for a decline in pipe music. Nevertheless, the result was the same for O’Reilly; he fell into abject poverty as piping was his only source of income. He had to seek refuge in the workhouse on a number of occasions in order to survive.

The foundation of the Gaelic League in 1894 was the ‘saving grace’ for O’Reilly as many of the old traditions in Irish music, dance and language were revived. O’Reilly being one of the most notable pipers of his day became a much sought-after entertainer. This resulted in him being invited to play in many parts of the country. He took part in various competitions organized by the Gaelic League; travelling to locations countrywide. O’Reilly travelled alone many times without aid of any kind, an extraordinary achievement on his part. He was also highly respected for his talent among the leading contemporary pipers. This ensured him a modest profit, something he had never really experienced during previous years. All the young pipers of the period were influenced by him and he tutored some of them. John Potts, who was affectingly known as ‘Old Potts’, had a nationwide reputation as a piper. In later years and would remove his hat when speaking of O’Reilly, an indication of the enormous respect he held for the man. John Moore was among the young pipers he tutored. Moore was born in, or near Galway about 1834. His father died while Moore was still a boy. His mother later remarried, this time to Martin O’Reilly. Peter Kelly was another young piper tutored by O’Reilly. Kelly was born in Galway and similar to O’Reilly he was blind from infancy. His parents insisted that he was taught to play the pipes by O’Reilly as a means of ensuring his future welfare.

From accounts by the great Seanchaí, Tomás Laighléis of Menlo, O’Reilly walked out from Sickeen to the village many times and played for the community there, just as Stephen Ruane would do a generation later. Rebellion leader, Eamonn Ceannt, was a great admirer of O’Reilly and said that he was among the greatest pipers of Ireland. Ceannt insisted on O’Reilly staying at his home when the old piper was performing in Dublin. Ceannt was himself an excellent piper and a founder member of the Dublin Pipers Club. Shortly after the Pipers Club was formed in 1901, Ceannt invited O’Reilly to the capital to play at the annual Feis. The competition was held in the large Concert Hall of the Rotunda. O’Reilly gave an excellent performance and his extraordinary talent was highly acclaimed in the Dublin newspapers. They mentioned that his selection, including The Battle of Aughrim, captured the emotion of all those present. The report stated that this ‘gallant old piper’ left the place throbbing with so much spirit that he could have led his countrymen into battle. He fired them up with a stirring and forceful version of the victorious march of Brian Boru. He played in perfect timing and tune and produced such marvellous tones that they lifted the entire audience with a vision of romantic Ireland throughout his performance. Another newspaper report stated that this ‘wonderful old man played the ancient airs with such a feeling of expression and profound understanding, that he simply took the house by storm’. Another report on his piping described the music in even more detail, stating again that his The Battle of Aughrim selection was so descriptive, people could see the advance of the armies on the battlefield. ‘They imagined the sound of British trumpets and the war cries of the Irish soldiers as they charged into the battle onslaught’. Even the wailing of the women, mothers and wives could be felt in his music. Aughrim was of course a lost field, but nothing daunted the gallant old piper, as the entertainer captivated everyone who heard the magic of his pipes. Needless to say, his performances won him first prize in the piping section.

Following this performance people flocked to hear him play, thus creating more demand for his music at events around the country. New and younger generations were influenced by his extraordinary talent. In February 1903, the Dublin Piper’s Club held a concert and an account of the event was published in The Gael. The following is an extract from the report: ‘Martin O’Reilly is our last truly great piper. His performance of the famous Fox Chase was a relic of old times. His Battle of Aughrim, a vividly descriptive piece of playing, is likely to be spoken of in Dublin Gaelic circles for many a long day. It is to be hoped this veteran blind piper may be given opportunities of displaying his skill during the coming year in all parts of Ireland’. Following one of his Dublin performances a priest named Fr Fielding took a photograph of O’Reilly. It later appeared on the cover of O’Neill’s Dance Music of Ireland.

That same year, 1903, he was invited to play at the Belfast Harp Festival where it was reported that he was the hero of the occasion. He held the audience almost spellbound and again played some of his own favourite pieces including The Fox Chase and other selections. Martin O’Reilly also continued to entertain audiences at home in Galway. It is known that he played for the people and children in Sickeen many times. The Gaelic League included him in all their major concerts, such as one they organised for the Town Hall in 1904. Among those present was another keen admirer of his music, Douglas Hyde, who would later become President of Ireland.

Despite all this recognition, he was again falling on hard times. For the most part, Martin O’Reilly lived constantly on the edge of poverty and hunger. This was highlighted by Francis O’Neill (1848–1936) an Irish-born American policeman who was a collector of traditional Irish music. O’Neill published a short biography of O’Reilly in 1913 and wrote, ‘Sightless and old and unable to make a living by other means than music, he was obliged, like many another unfortunate Irish minstrel, to take refuge in the poorhouse as his only escape from starvation’. As old age was approaching O’Reilly was affected by health issues which eventually forced him out of business and he again had to enter the workhouse. It is a sobering and somewhat poignant thought to see how this exceptionally talented old musician had to end his days in such poverty. One man, who knew him well, later wrote, ‘When we come to consider the heartless indifference of the people towards Martin O’Reilly and his talents, can we be blamed if we sometimes question the sincerity of the agitators who have talked themselves hoarse in their support of a regenerated Ireland?’ After all his incredible achievements and once the excitement had subsided O’Reilly found himself at the mercy of the elements without any support. This great old traditional musician should have been given due recognition. A great opportunity was lost in having him teach his precious art of piping to another generation, which could have sustained him. Instead, he had to seek refuge in a workhouse, a place that people avoided and would only consider in absolutely dreadful circumstances, starving, homeless and destitute. This was his fate, Martin O’Reilly died in the Gort Poorhouse in 1904 without the acknowledgement he deserved. Tradition tells us that while lying on his deathbed the last request he made was to ask for his beloved pipes. It would be wonderful to see Martin O’Reilly acknowledged and remembered in Galway, perhaps a plaque on the old building in Sickeen.